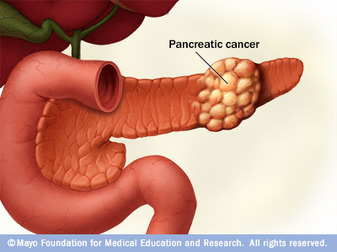

Pancreatic cancer is a malignant neoplasm originating from transformed cells arising in tissues forming the pancreas. The most common type of pancreatic cancer, accounting for 95% of these tumors, is adenocarcinoma (tumors exhibiting glandular architecture on light microscopy) arising within the exocrine component of the pancreas. A minority arise from islet cells, and are classified as neuroendocrine tumors. The signs and symptoms that eventually lead to the diagnosis depend on the location, the size, and the tissue type of the tumor, and may include abdominal pain, lower back pain, and jaundice (if the tumor compresses the bile duct).

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and the eighth worldwide. Pancreatic cancer has a poor prognosis: for all stages combined, the 1- and 5-year relative survival rates are 25% and 6%, respectively; for local disease the 5-year survival is approximately 20% while the median survival for locally advanced and for metastatic disease, which collectively represent over 80% of individuals, is about 10 and 6 months respectively.

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and the eighth worldwide. Pancreatic cancer has a poor prognosis: for all stages combined, the 1- and 5-year relative survival rates are 25% and 6%, respectively; for local disease the 5-year survival is approximately 20% while the median survival for locally advanced and for metastatic disease, which collectively represent over 80% of individuals, is about 10 and 6 months respectively.

Signs and Symptoms

Early pancreatic cancer often does not cause symptoms, and the later symptoms are usually nonspecific and varied. Therefore, pancreatic cancer is often not diagnosed until it is advanced. Common symptoms include:

- Pain in the upper abdomen that typically radiates to the back (seen in carcinoma of the body or tail of the pancreas)

- Loss of appetite (anorexia) or nausea and vomiting

- Significant weight loss (cachexia)

- Painless jaundice (yellow tint to whites of eyes or yellowish skin in serious cases, possibly in combination with darkened urine) when a cancer of the head of the pancreas (75% of cases) obstructs the common bile duct as it runs through the pancreas. This may also cause pale-colored stool and steatorrhea. The jaundice may be associated with itching as the salt from excess bile can cause skin irritation.

- Trousseau sign, in which blood clots form spontaneously in the portal blood vessels, the deep veins of the extremities, or the superficial veins anywhere on the body, may be associated with pancreatic cancer.

- Diabetes mellitus, or elevated blood sugar levels. Many patients with pancreatic cancer develop diabetes months to even years before they are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, suggesting new onset diabetes in an elderly individual may be an early warning sign of pancreatic cancer.

- Clinical depression has been reported in association with pancreatic cancer, sometimes presenting before the cancer is diagnosed. However, the mechanism for this association is not known.

- Symptoms of pancreatic cancer metastasis. Typically, pancreatic cancer first metastasizes to regional lymph nodes, and later to the liver or to the peritoneal cavity and, rarely, to the lungs; it rarely metastasizes to bone or brain.

Risk Factor

Risk factors for pancreatic cancer may include:

- Family history: 5–10% of pancreatic cancer patients have a family history of pancreatic cancer. The genes have not been identified. Pancreatic cancer has been associated with the following syndromes: autosomal recessive ataxia-telangiectasia and autosomal dominantly inherited mutations in the BRCA2 gene and PALB2 gene, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome due to mutations in the STK11 tumor suppressor gene, hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (Lynch syndrome), familial adenomatous polyposis, and the familial atypical multiple mole melanoma-pancreatic cancer syndrome (FAMMM-PC) due to mutations in the CDKN2A tumor suppressor gene. There may also be a history of familial pancreatitis.

- Age. The risk of developing pancreatic cancer increases with age. Most cases occur after age 60, while cases before age 40 are uncommon.

- Smoking. Cigarette smoking has a risk ratio of 1.74 with regard to pancreatic cancer; a decade of nonsmoking after heavy smoking is associated with a risk ratio of 1.2.

- Diets low in vegetables and fruits

- Diets high in red meat. Processed meat consumption is positively associated with pancreatic cancer risk, and red meat consumption was associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer in men.

- Diets high in sugar-sweetened drinks (soft drinks). In particular, the common soft drink sweetener fructose has been linked to growth of pancreatic cancer cells.

- Obesity

- Diabetes mellitus is both risk factor for pancreatic cancer, and, as noted earlier, new onset diabetes can be an early sign of the disease.[clarification needed how much]

- Chronic pancreatitis has been linked, but is not known to be causal. The risk of pancreatic cancer in individuals with familial pancreatitis is particularly high.

- Helicobacter pylori infection

- Gingivitis or periodontal disease

Treatment

Exocrine pancreas cancer

Surgery

Treatment of pancreatic cancer depends on the stage of the cancer. Although only localized cancer is considered suitable for surgery with curative intent at present, only ~20% of cases present with localised disease at diagnosis. Surgery can also be performed for palliation, if the malignancy is invading or compressing the duodenum or colon. In such cases, bypass surgery might overcome the obstruction and improve quality of life but is not intended as a cure.

The Whipple procedure is the most common attempted curative surgical treatment for cancers involving the head of the pancreas. This procedure involves removing the pancreatic head and the curve of the duodenum together (pancreato-duodenectomy), making a bypass for food from stomach to jejunum (gastro-jejunostomy) and attaching a loop of jejunum to the cystic duct to drain bile (cholecysto-jejunostomy). It can be performed only if the patient is likely to survive major surgery and if the cancer is localized without invading local structures or metastasizing. It can, therefore, be performed in only the minority of cases.

Cancers of the tail of the pancreas can be resected using a procedure known as a distal pancreatectomy. Recently, localized cancers of the pancreas have been resected using minimally invasive (laparoscopic) approaches.

After surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine has been shown in several large randomized studies to significantly increase the 5-year survival (from approximately 10 to 20%), and should be offered if the patient is fit after surgery (Oettle et al. JAMA 2007, Neoptolemos et al. NEJM 2004, Oettle et al. ASCO proc 2007).

Radiation

Principles of radiation therapy in pancreas adenocarcinoma are reviewed extensively in guidelines by the NCCN. Radiation can be considered in several situations. One situation is the addition of radiation therapy after potentially curative surgery. Groups in the US have been more apt to use adjuvant radiation therapy than groups in Europe.

Chemotherapy

In patients not suitable for resection with curative intent, palliative chemotherapy may be used to improve quality of life and gain a modest survival benefit. Gemcitabine was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 1998, after a clinical trial reported improvements in quality of life and a 5-week improvement in median survival duration in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. This marked the first FDA approval of a chemotherapy drug primarily for a nonsurvival clinical trial endpoint. Gemcitabine is administered intravenously on a weekly basis.

A Canadian-led Phase III randomised controlled trial, reported in 2005, involved 569 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, led the US FDA in 2005 to license erlotinib (Tarceva) in combination with gemcitabine as a palliative regimen for pancreatic cancer. This trial compared the outcome of gemcitabine/erlotinib to gemcitabine/placebo, and demonstrated improved survival rates, improved tumor response and improved progression-free survival rates. Other trials are now investigating the effect of the above combination in the adjuvant (post surgery) and neoadjuvant (pre-surgery) settings.

Addition of oxaliplatin to Gemcitabine (Gem/Ox) was shown to confer benefit in small trials, but is not yet standard therapy.

Surgery

Treatment of pancreatic cancer depends on the stage of the cancer. Although only localized cancer is considered suitable for surgery with curative intent at present, only ~20% of cases present with localised disease at diagnosis. Surgery can also be performed for palliation, if the malignancy is invading or compressing the duodenum or colon. In such cases, bypass surgery might overcome the obstruction and improve quality of life but is not intended as a cure.

The Whipple procedure is the most common attempted curative surgical treatment for cancers involving the head of the pancreas. This procedure involves removing the pancreatic head and the curve of the duodenum together (pancreato-duodenectomy), making a bypass for food from stomach to jejunum (gastro-jejunostomy) and attaching a loop of jejunum to the cystic duct to drain bile (cholecysto-jejunostomy). It can be performed only if the patient is likely to survive major surgery and if the cancer is localized without invading local structures or metastasizing. It can, therefore, be performed in only the minority of cases.

Cancers of the tail of the pancreas can be resected using a procedure known as a distal pancreatectomy. Recently, localized cancers of the pancreas have been resected using minimally invasive (laparoscopic) approaches.

After surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine has been shown in several large randomized studies to significantly increase the 5-year survival (from approximately 10 to 20%), and should be offered if the patient is fit after surgery (Oettle et al. JAMA 2007, Neoptolemos et al. NEJM 2004, Oettle et al. ASCO proc 2007).

Radiation

Principles of radiation therapy in pancreas adenocarcinoma are reviewed extensively in guidelines by the NCCN. Radiation can be considered in several situations. One situation is the addition of radiation therapy after potentially curative surgery. Groups in the US have been more apt to use adjuvant radiation therapy than groups in Europe.

Chemotherapy

In patients not suitable for resection with curative intent, palliative chemotherapy may be used to improve quality of life and gain a modest survival benefit. Gemcitabine was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 1998, after a clinical trial reported improvements in quality of life and a 5-week improvement in median survival duration in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. This marked the first FDA approval of a chemotherapy drug primarily for a nonsurvival clinical trial endpoint. Gemcitabine is administered intravenously on a weekly basis.

A Canadian-led Phase III randomised controlled trial, reported in 2005, involved 569 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, led the US FDA in 2005 to license erlotinib (Tarceva) in combination with gemcitabine as a palliative regimen for pancreatic cancer. This trial compared the outcome of gemcitabine/erlotinib to gemcitabine/placebo, and demonstrated improved survival rates, improved tumor response and improved progression-free survival rates. Other trials are now investigating the effect of the above combination in the adjuvant (post surgery) and neoadjuvant (pre-surgery) settings.

Addition of oxaliplatin to Gemcitabine (Gem/Ox) was shown to confer benefit in small trials, but is not yet standard therapy.

Prevention

Almost 8 percent of people with pancreatic cancer have had the disease strike family members, research has found. According to a national database of people with pancreatic cancer, people with two first-degree relatives (parents, siblings or children) with the disease have an 18-fold higher risk. People with three relatives with the disease have a 57-fold higher risk. Researchers have found that mutations in several genes can raise the risk of the disease. And while you can't do anything about the genes you are born with, changing some other factors that you do have control over can help reduce your risk. The following issues may help influence whether or not you get pancreatic cancer:

Acute pancreatitis can turn chronic, or long-lasting, often because of heavy alcohol use. However, chronic pancreatitis can also be inherited.

People with chronic pancreatitis have a higher risk of developing pancreatic cancer, especially if they inherit the condition. These people have a 40 percent chance of developing pancreatic cancer by the age of 70.

Even if you're at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes, you can prevent it or delay it by losing 5 percent to 10 percent of your body weight and getting 30 minutes of physical activity each day, according to the American Diabetes Association.

Making some positive lifestyle changes, such as not smoking, eating healthier foods, incorporating exercise into your daily routine, and reducing the amount of alcohol you drink, can all add up to a healthier life — and a lower risk of pancreatic cancer, no matter what your family history.

Sources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pancreatic_cancer

http://www.webmd.com/cancer/pancreatic-cancer/pancreatic-cancer-treatments-stage

http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/pancreatic/Patient/page4

http://www.everydayhealth.com/pancreatic-cancer/risk-factors.aspx

- Smoking. Smoking doubles your risk of pancreatic cancer. Researchers have found that smoking accounts for the disease in about 25 percent of patients. If you want to slash your risk of the disease — which kills three out of four patients within a year — not smoking would be a great place to begin.

- Diet and exercise. A diet high in meat — especially if it's grilled, barbecued, or broiled — has been linked to a higher risk of pancreatic cancer, at least in men. On the other hand, a diet containing lots of fruits and vegetables may lower your risk. Also, obesity and lack of physical activity have been associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer.

- Pancreatitis. This condition, in which the pancreas becomes inflamed, can raise your risk of pancreatic cancer sharply. There are two types of pancreatitis: acute and chronic. Acute pancreatitis usually goes away in a few days. It is often caused by gallstones or alcohol abuse, according to the American Gastroenterological Association. Other causes include infections and medications.

Acute pancreatitis can turn chronic, or long-lasting, often because of heavy alcohol use. However, chronic pancreatitis can also be inherited.

People with chronic pancreatitis have a higher risk of developing pancreatic cancer, especially if they inherit the condition. These people have a 40 percent chance of developing pancreatic cancer by the age of 70.

- Diabetes. Having type 2 diabetes (which is associated with obesity and a sedentary lifestyle) may double your risk of pancreatic cancer. However, type 1 diabetes, the type in which the body destroys insulin-making cells in the pancreas, is not linked to this cancer risk.

Even if you're at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes, you can prevent it or delay it by losing 5 percent to 10 percent of your body weight and getting 30 minutes of physical activity each day, according to the American Diabetes Association.

Making some positive lifestyle changes, such as not smoking, eating healthier foods, incorporating exercise into your daily routine, and reducing the amount of alcohol you drink, can all add up to a healthier life — and a lower risk of pancreatic cancer, no matter what your family history.

Sources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pancreatic_cancer

http://www.webmd.com/cancer/pancreatic-cancer/pancreatic-cancer-treatments-stage

http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/pancreatic/Patient/page4

http://www.everydayhealth.com/pancreatic-cancer/risk-factors.aspx